About Mosquitoes

Mosquitoes belong to the insect order Diptera, or flies, with about 140 species in North America. They thrive in various aquatic habitats, from saltwater to freshwater. Throughout history, mosquito-borne diseases have shaped civilizations, hindering the Romans, Greeks, and Crusaders, as well as early American colonization and the construction of the Panama Canal. In 1935, the U.S. still recorded 900,000 malaria cases.

Today, mosquitoes are well known for spreading diseases. They transmit viruses like West Nile and encephalitis through a bird-mosquito cycle, affecting humans, horses, and even dogs through canine heartworm. Some people also suffer allergic reactions to bites, which can lead to secondary infections.

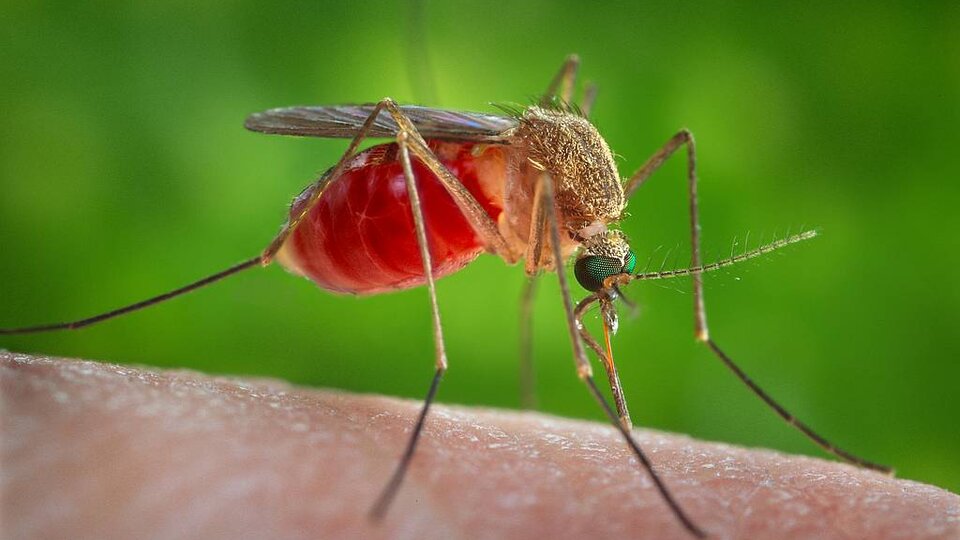

Beyond health risks, mosquitoes are a major nuisance, disrupting outdoor activities. Only female mosquitoes bite, using their piercing-sucking mouthparts to draw blood. Males, with feathery antennae, feed on nectar. When a female bites, she injects saliva containing anticoagulants and, potentially, disease-causing organisms from previous hosts, spreading infections across birds, animals, and humans.

Mosquito Life Cycle

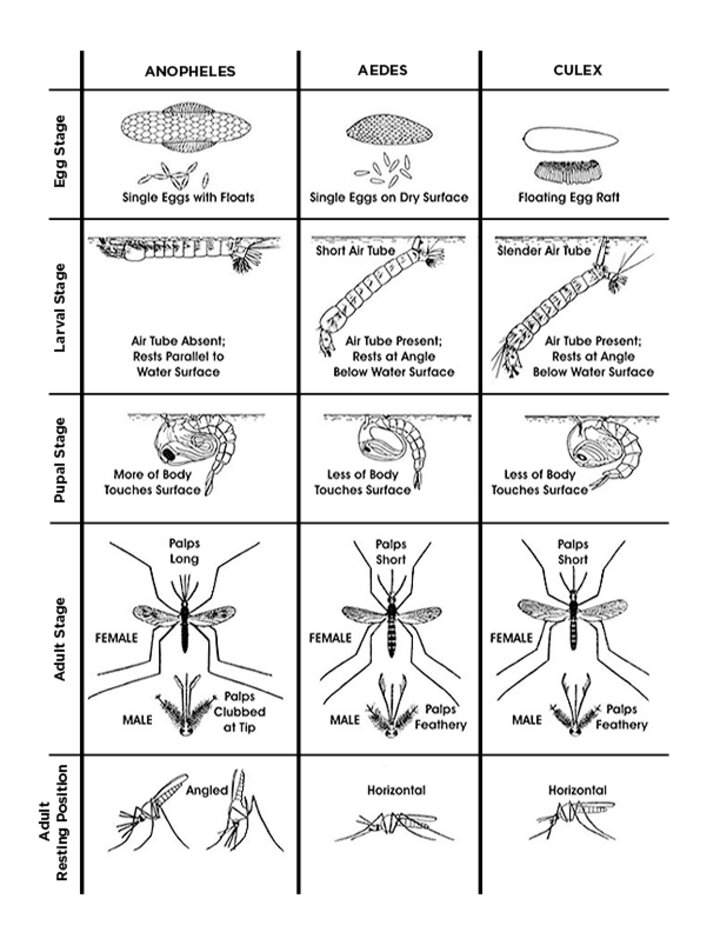

Mosquitoes go through four stages: egg, larva ("wiggler"), pupa ("tumbler"), and adult. Eggs are laid on water, soil, or vegetation and can hatch immediately or stay dormant for years until conditions are right.

Larvae, called wigglers, swim in an "S-shaped" motion and hang head-down at the water’s surface, using a breathing tube to get air. They molt four times before becoming pupae. Pupae, or tumblers, don’t feed but move by tumbling into deeper water when disturbed. After 2-3 days, the adult mosquito emerges.

Females live about two weeks, flying several miles if needed. They lay hundreds of eggs in batches between blood meals.

Mosquito Surveys

After flooding, communities may form mosquito survey teams to track mosquito development and assist city mosquito control efforts. Volunteers can identify breeding sites by inspecting stagnant water, such as roadside ditches, oxbows, and areas with aquatic vegetation. Moving water and wave-exposed lakes are less likely habitats.

Sampling is done using a dipper on a handle to collect water and check for larvae or pupae—counts of 8-10 per dip indicate concern. Keeping records of standing water, vegetation, and mosquito stages helps predict outbreaks. Large larvae and tumblers signal an imminent emergence, while many male mosquitoes in the evening suggest a nearby breeding site. Urban areas should monitor water-holding items like birdbaths, clogged gutters, and discarded containers.

Mosquito Identification

The most common mosquito genera are Anopheles (active day and night, breeding in both permanent and flood waters), Aedes (daytime biters that breed in flood waters), and Culex (evening and dusk feeders that breed in both flood and permanent waters).

References

We have drawn information from the following references in developing this material:

- Anonymous, 1967. CDC Manual. Pictorial Keys. Arthropods, Reptiles, Birds and Mammals of Public Health Significance. US/HEW, Public Health Service. 192 pp.

- Anonymous, 1986. Modern Mosquito Control. The Problem/The Solution. Sixth Ed., American Cyanamid Company. 35 pp.

- Kramer, W. 1993. Environmental Health Circular. Bureau of Environmental Health. Nebraska Department of Health.

- Lewis, Don, 1993. Horticulture and Home Pest Newsletter. July 21, 1993. Mosquito Control Following the Floods of '93.

- Mock, D.E. and L. Brooks. Kansas Insect Newsletter. May 21, 1993.